Contents

Other Works on Paper

Food & Planets

This page text onlyGallery

Click on any image for a larger view. Then click "back" to return to this page.

Did you come to this site in a frame? Want to get out? Click here!

Related site:

ArtGods

Plexiglas

The Metamorphosis of FrogFred

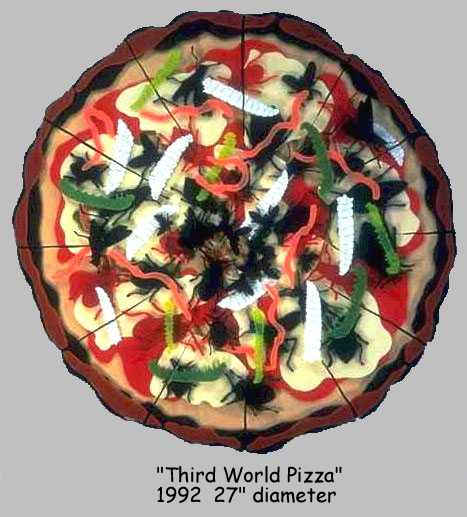

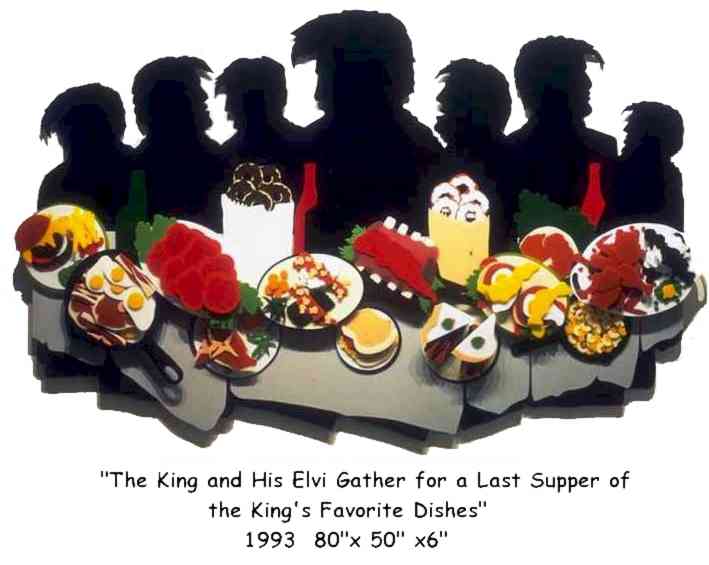

David Gilhooly has given up clay. The last time he gave it up was in 1983. The artist had also given up making frogs at that time. He began using Plexiglas as a medium and had the intention of only doing a few clay pieces on a commission basis, but he found he had a sketchbook of "unfinished business" that he wanted to complete before he could move on. These pieces included the food pieces sans frogs which were made up until 1993, as well as the planet pieces, the last of which being Tiki Moon Rising.

Critics of David Gilhooly's work often site the colorful qualities of his glazing. Words like loud,

excessive, and garish; meant to deride and possibly discourage the artist had always spurred him on. It is no wonder that when tiring of clay, he turned to Plexiglas. Plexiglas has a long history of use as a commercial medium for signs and advertising. It's colors are loud, excessive and garish.

Plexiglas is a hard acrylic material that comes in sheets that are faced on both sides with a brown paper

masking to keep the material from being scratched in handling. It is available in clear, opaque colors, transparent colors and in a variety of thicknesses. The manufacturer, Rohm and Haas, says that their product will not fade, crack or chip under normal conditions.

"I liked the colors Plexiglas came in even though it was a challenge to use a very limited palette. I enjoyed using a medium that lent itself to

flat objects, like signs. With Plexiglas I had to change my entire way of working. I had to work more cleanly. My tools had to be kept clean so as not to scratch the material. My studio got neater and more tidy. I had to work carefully. The exchange for that was being able to consider the transparent nature of the material, the colored shadows

that it would create on the wall, the way the viewer was reflected in the face of the work, and the way the layers of color would change with the light. But the real difficulty was working in the dark, so to speak. I could never really tell what a piece would look like until the final unmasking of all the different elements. I knew what colors I was

working with, but could never really tell how they interacted with each other until I took the brown paper masking off each part of the piece."

By layering the various panes of Plexiglas Gilhooly was able to take advantage of the medium's transparent qualities. In many of the pieces (e.g. Nuclear Honolulu) the viewer can see through the first layer of Plexiglas and get a hint or shadow of images that lie under it.

The studio is bereft of clay and glazes; the kilns are gone. Slab roller, wedging tables, glaze brushes, fettling knives, etc. have been sold or given away to make room for saws, sanders and storage space for new materials. The dialog has remained the same. The artist still comments on food, consumerism, religion, mythology, etc. using Plexiglas as his voice.

Gilhooly always had an intense love of found objects.

The artists that he admired most were the artists who could use found objects as their palettes. In fact, his earliest work was bronze sculpture using the "lost objects" technique of casting, but he never felt that he could successfully include found objects in ceramic sculpture. Plexiglas lent itself to

the use of plastic found objects. The artist found that he could incorporate things like plastic fruit and vegetables into a Plexiglas sculpture and have the piece work visually. He graduated to restaurant display food and then to plastic objects. Finally, he found that he could include things like real dog food, breakfast cereal and snack

foods. But he soon found that this was not his ideal way of working.

"It was too much work. I'd have to cut out all the pieces and then finish the edges and put the piece together. There was too much time between the concept and the realization of the actual piece. I spent too much time sanding the edges with different grades of sandpaper and finally with steel wool because I didn't want to spend umpty-three million dollars on a hydrogen cutter. Sometimes while sanding I'd break off a piece and have to figure out a way to make it work. Then when I took off the masking I'd sometimes find that the colors didn't work well together, so I'd have to break something off or start again. Not being able to know what a piece looked like while working on it was a real handicap."

David Gilhooly would undergo yet another change in his method of working.

Last revised December 3,1999